How do you judge a manager?

They get judged practically every minute of every match, and certainly after every match. Either they didn’t make the right substitutions, or the formation wasn’t right or the set pieces didn’t make any sense, but a manager needs to deliver in almost every way to receive a positive mention. Most importantly, they need to deliver three points.

It is a results business. We hear this over and over again, points are the currency by which rewards come in football. Essentially that is what the managers’ primary responsibility is, improving the team’s points won to the extent that improvement can be seen in the league table. The problem is that, in reality, it is not that simple.

What if, for instance, a club runs into financial difficulty? What if the club decides to sell its best footballers? What if a new stadium is planned and constraints on the playing budget are imposed? Dare I say, what if the team are unlucky? Does style of play matter? So, whilst getting points on the board is absolutely important, is judging a manager by results alone a good strategy?

Judging a manager’s talent and ability is something that I, and many other much more well respected football types, find very difficult to do. It is precisely because of the multi-faceted, aspects out of the sphere of control of managers (they aren’t even on the pitch to affect things there) that means that labelling a manager as awful or even outstanding, is often a fool’s game. Except with Steve Kean and Jurgen Klopp/Pep Guardiola. Even Owen Coyle won promotion into the Premier League and has recently won another trophy in the Indian Super League.

Having said that, I would like to investigate a few ideas.

- Is the club’s position in the ladder better or worse than when they joined?

- Does the playing staff look a better group at the end of the tenure?

- Could the player recruitment be described as over 50% effective?

- What has the financial management at the club been like in terms of transfer and wage spend?

- Has there been any infrastructure improvement in the club?

- Are there any assets left behind that may allow the club to progress at the end of the tenure?

- What is/has the relationship between the fans and the manager like/been like?

- Positive performance data

Blackburn Rovers are in the situation where their manager is leaving after just over 5 years in the hot seat. This gives us a really good, large sample to look at a club’s performance during a manager’s tenure and assess the body of work that they have produced.

Tony Mowbray was appointed to succeed Owen Coyle on 22nd February 2017. His first match in charge of Rovers was the next Saturday where Rovers drew 1-1 with Burton Albion in the Championship.

At this stage allow me to introduce the first couple of areas of investigation:

Did Blackburn Rovers improve their position in the ladder under Mowbray’s management?

An obvious yes. At the time of appointment Blackburn Rovers were 23rd in The Championship, Mowbray leaves after guiding them to an 8th place finish.

Then:

Mowbray was initially unable to save Blackburn from relegation from this point, eventually being relegated on goal difference with a points tally of 51. This points total would’ve seen Blackburn finish 19th in 2021/22. Mowbray managed a points per game ratio of 1.47 compared to Owen Coyle’s 0.94 in the opening 31 matches with the same players.

Now:

Mowbray brought Blackburn back into the Championship at the first time of asking, finishing 2nd in League One to Wigan Athletic. He went on to achieve 15th, 11th, 15th placed finishes before finishing in 8th in 2011/2012.

Since promotion back to the Championship Blackburn only once finished a round of fixtures inside the relegation zone (after Week 2 of 2019/20) and they completed over 30 weeks inside the top 6, four of which were inside the top 2 in 2021/22.

Despite this Blackburn Rovers finished each season poorly and were never in with a shout of promotion in the final week of the season.

Does the playing staff look a better group at the end of the tenure?

The starting XI selected by Mowbray for his first match in charge is shown below.

Added to this XI we must consider other squad members available to Mowbray.

Premier League goalkeeper & Spanish international David Raya was in the squad and was Mowbray’s first choice goalkeeper in League One and then initially in the Championship as well. In retrospect it became a real positive that so many of this squad were out of contract in 2017 as it allowed Mowbray to bring in a fresh set of players alongside the likes of Mulgrew, Lenihan, Nyambe, Graham and Elliott Bennett. However, that is a rebuild that could’ve happened in the Championship given better circumstances.

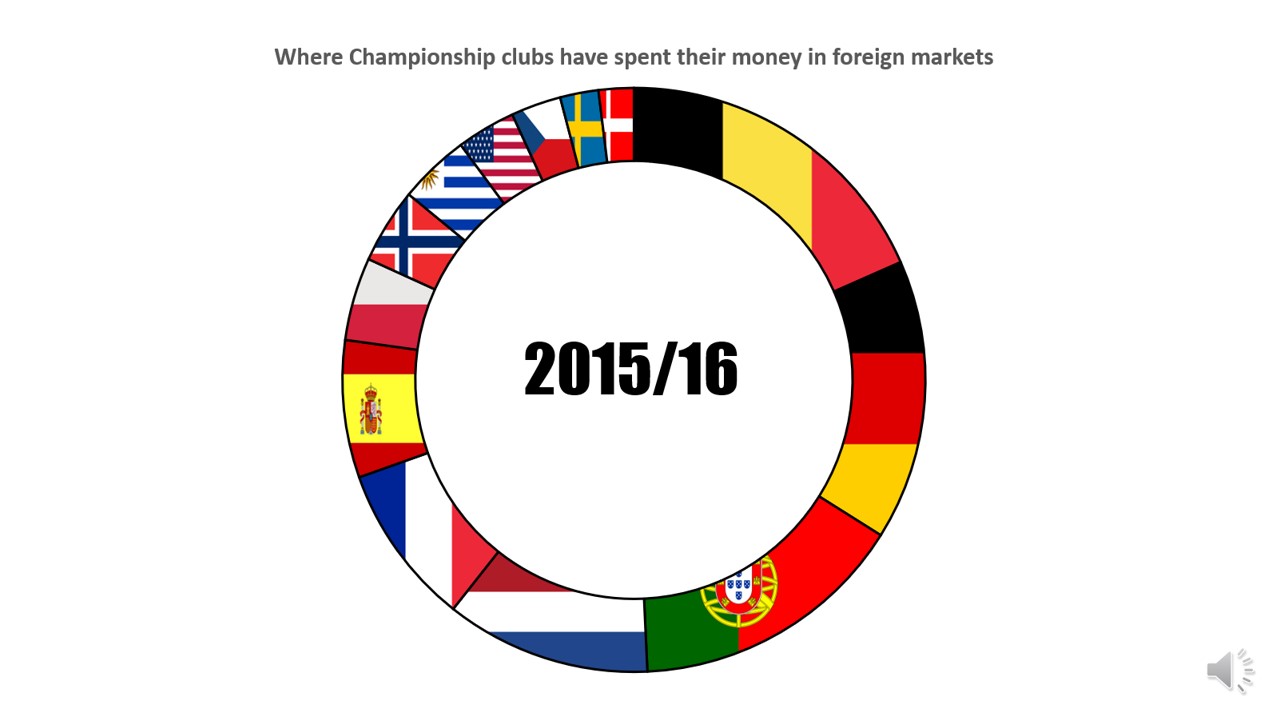

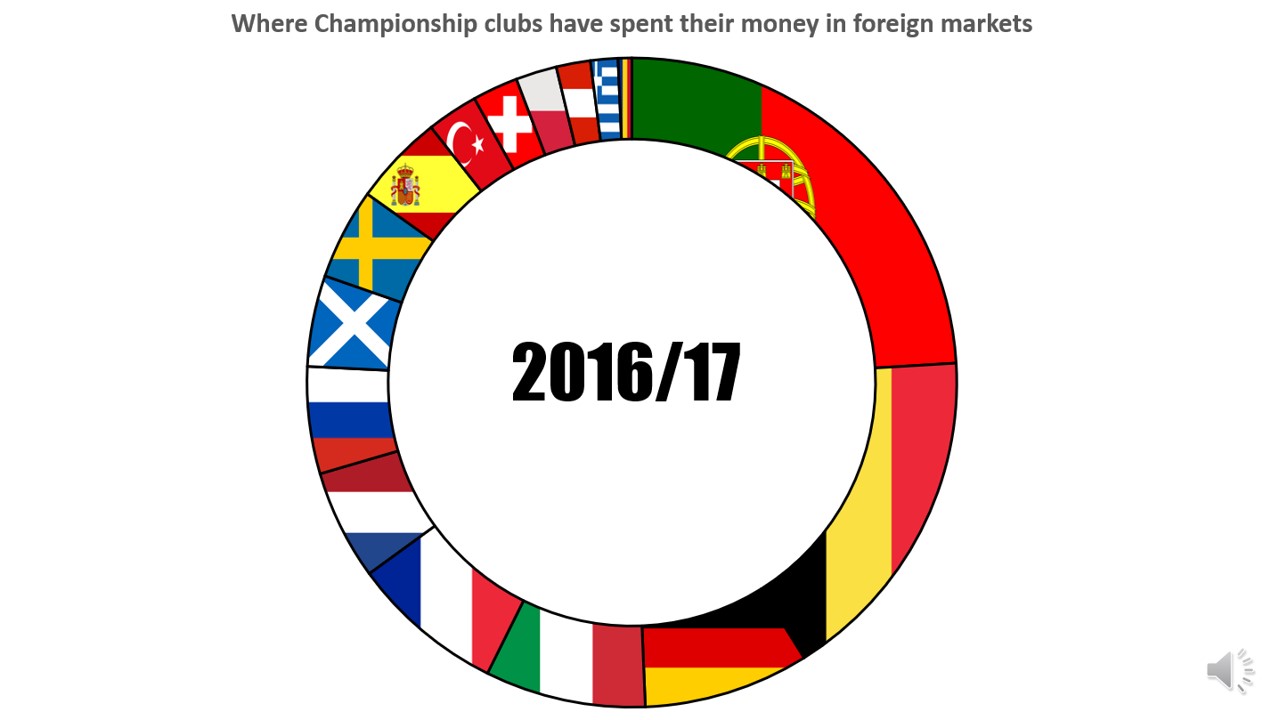

Comparing the squad he began with to the squad Mowbray worked with this season we can see a massive evolution. Though not obvious in this image, the squad is much younger (proven later on) but also much more depth and tactical flexibility to it. There can be little doubt that this squad is much stronger than when Mowbray took charge.

However, we must also consider what is left behind. There is a lot of red and yellow in the diagram above, those players will not be available to the next manager.

This is the squad that has been left behind by Tony Mowbray. It has been announced today that the Ben Brereton Diaz contact extension has been activated by the club so he has twelve months left on his current deal.

There are some definite depth issues that need to be corrected by the new regime, but the first 11-15 players on the teamsheet here are a) experienced Championship level players and b) many have growth yet to come. Most of the players who have long term deals have a lot of upside and value, with players that are a bit older on short term deals (Ayala & Dack).

There is a lot of flexibility that can be done around this core group of players. If the new manager wants to play a back 4 or back 3, wide forwards or a front two, then that can all be done, with some good recruitment.

There is also a very talented crop of young players in behind. A few are on the graphic, but not mentioned are the likes of Lenni Cirino, Jared Harlock, Jake Batty, Georgie Gent, Charlie Weston, Harrison Wood, and Jordan Eastham. Many others that have a chance of developing into first team squad members as well.

Rovers used the second youngest group of players in the division behind relegated Barnsley. This group has a good chance of developing together given the right circumstances and guidance from a new coaching setup.

The 16/17 squad that Mowbray inherited had an average age 2 years higher and was ranked 14th youngest in the division.

The squad is assessed by Transfermarkt as the 9th highest valued squad in the division. We can take this with a pinch of salt as not all values are accurate but is a decent general guide to where the squad is at in terms of valuable players.

Compare this to where Transfermarkt assessed the squad that Mowbray took over and there is a vast difference. This squad was ranked 18th in the Championship, a full £15m less valuable than the current squad.

So Mowbray passes the first two tests with flying colours. Just taking the squad value and breaking that down slightly, are there any assets within that squad that can allow Blackburn Rovers to progress?

Ben Brereton Diaz is much rumoured to be moving on in the summer. The 22 year old has only twelve months left on his contract and has come to international recognition due to his exploits for Chile in the last year or so. He used that impetus to have his best ever goalscoring season in domestic football, scoring 22 league goals in 2021/22. Some other players who may well attract good money in the transfer market include Academy products John Buckley (now proven at first team level) and 17 year old central defender Ash Phillips. Whilst Mowbray cannot be credited with Phillips’ development, he can be attributed to encouraging the development of the Academy and ensuring that the Category 1 status remained vital to the club during his tenure.

As we have seen, the majority of the players are young and therefore have resale value. Harry Pickering, Scott Wharton, Hayden Carter, Tayo Edun, Lewis Travis, Sam Gallagher, Tyrhys Dolan and countless Academy products provide examples of players that have value for the club. This is in stark contrast to the situation that Mowbray found when he arrived.

However, this is not to say that the recruitment has been infallible. Mowbray did often quote that a manager “lives and dies by their recruitment” and his stock line was that in each transfer window he wanted to “leave the squad in a better place than at the beginning of the window”, which is a pretty vacuous and vague statement, whilst being totally correct.

Judging managers on recruitment is often a red herring though in the modern game. In the age of big data and large recruitment teams at clubs recruitment is often out of the managers’ hands, at least until a stage quite far down the road. Also, in a Director of Football/Head Coach model, recruitment may be almost totally out of the head coach’s hands and his job is to deal with the hand that they are given.

However, it is of huge importance (in my opinion) that the manager/head coach works closely with the recruitment team to ensure that the team fully understands their principles of play and their assessment of the current squad. This way there is little wastage of time and also ensures that the players shortlisted for a transfer window are (hopefully) of the right type to improve the squad that the coach can work with.

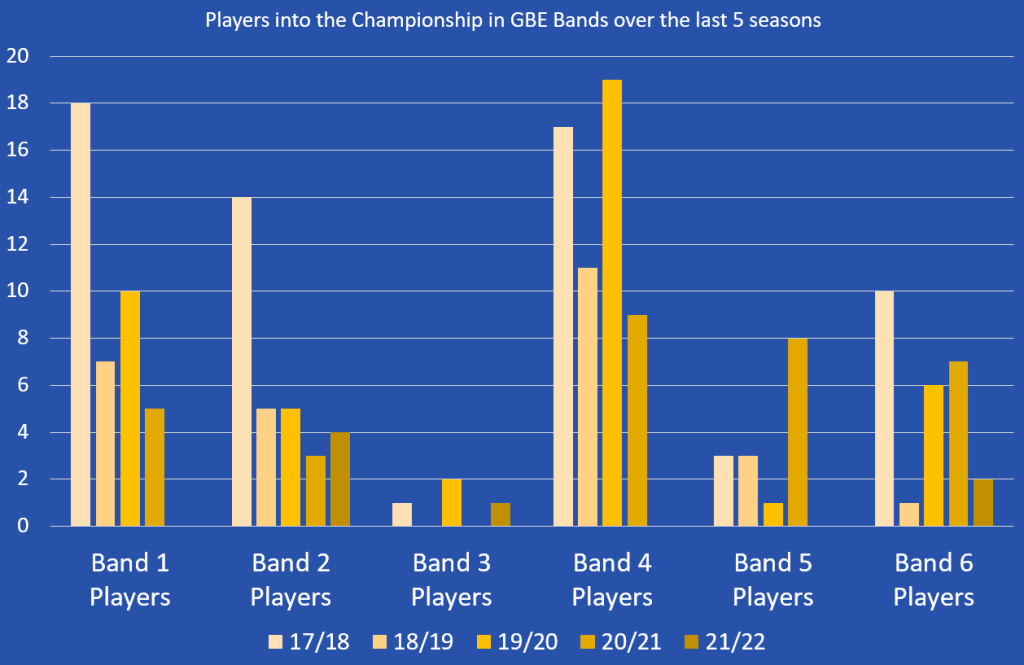

So, could the player recruitment at Blackburn under Mowbray be described as over 50% effective?

Why 50%? Dr. Ian Graham of Liverpool gave a presentation at the Statsbomb Conference in 2021 discussing how how many factors build into transfers in football. With all the complications, getting over half of them ‘right’ is a pretty useful ratio.

Forgive me, but there is an element of subjectivity to this measure in this instance. Whilst I would love to have the time to build an effective model to independently assess the success of transfers (and I have given plenty of thought as to how this would look) I simply don’t have the time to make this work right now.

So, taking into account a number of factors, but principally:

- Percentage of minutes played

- Impact on results

- Impact on performances

- Resale value

- Profit or loss made on transfer fee

- Value for wages

- Fan connection

Taking all transfers into account and judging each one as an absolute success or failure, I came down on the following:

The full list of who were judged successes and failures are at the bottom of the blog as an appendix in case you want to disagree!

Mowbray just about hits the 50% that Ian Graham suggested for all transfers, and just below on the permanent ones. Of course, this lacks context, a couple of the signings have been magnificent. Bradley Dack is the archetypal example of this. A player signed for £750k that was due to be sold for £10m+ before his terrible injuries. Adam Armstrong turned a near £10m profit for the club and Ben Brereton Diaz looks like he may do similarly this summer. Many of the signings included in the sample were for young players who were small risks and really shouldn’t be weighted the same as the senior transfers.

It hasn’t all been sunshine and roses however. Daniel Ayala’s transfer hasn’t worked out at all and he continues to be under contract at the club taking a big wage. Lewis Holtby can be filed under a similar heading. Meanwhile, players like Sam Hart, Brad Lyons, Mitch Candlin, and Antonis Stergiakis haven’t made an impact on the first team.

Overall, it is a net positive for Mowbray that in his tenure the recruitment has concentrated on young players with potential resale value and/or that provide a lot of service for the club.

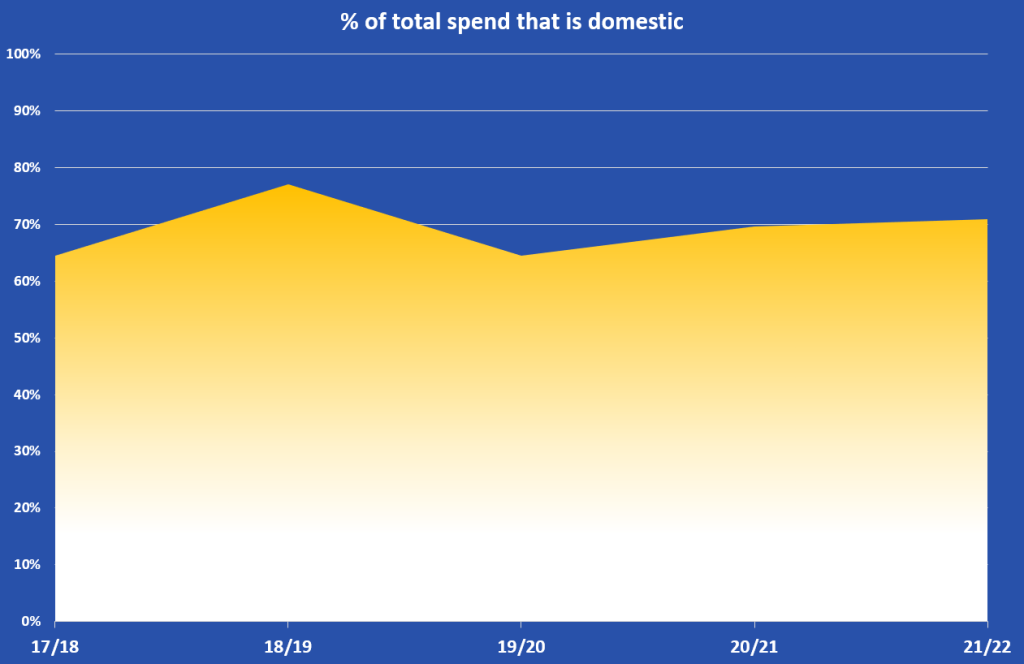

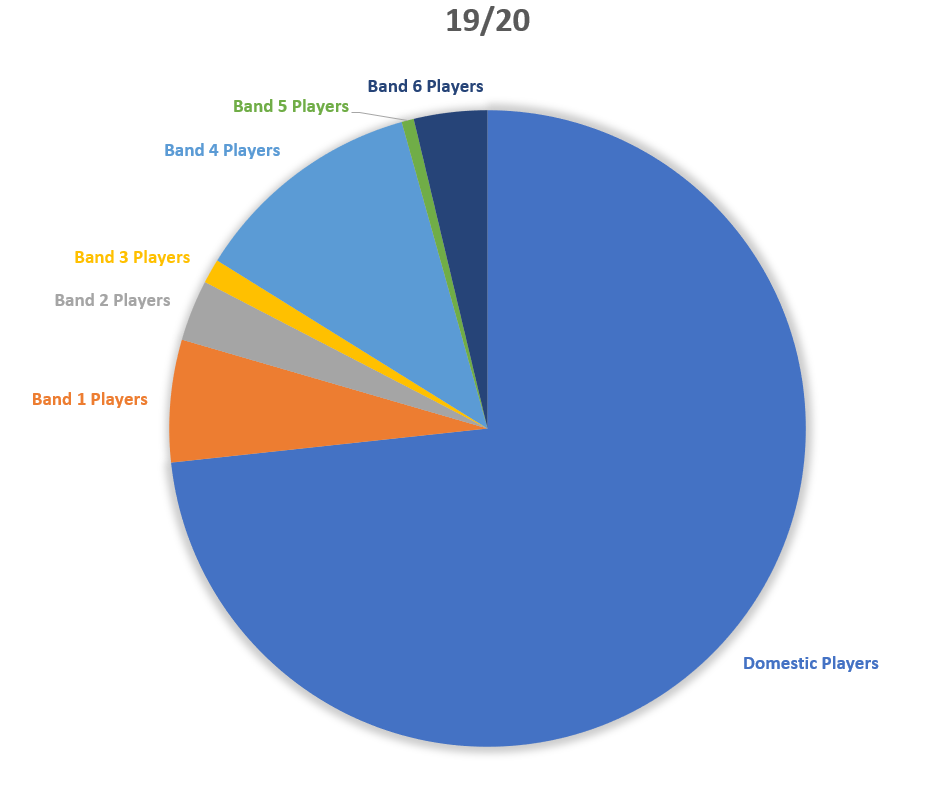

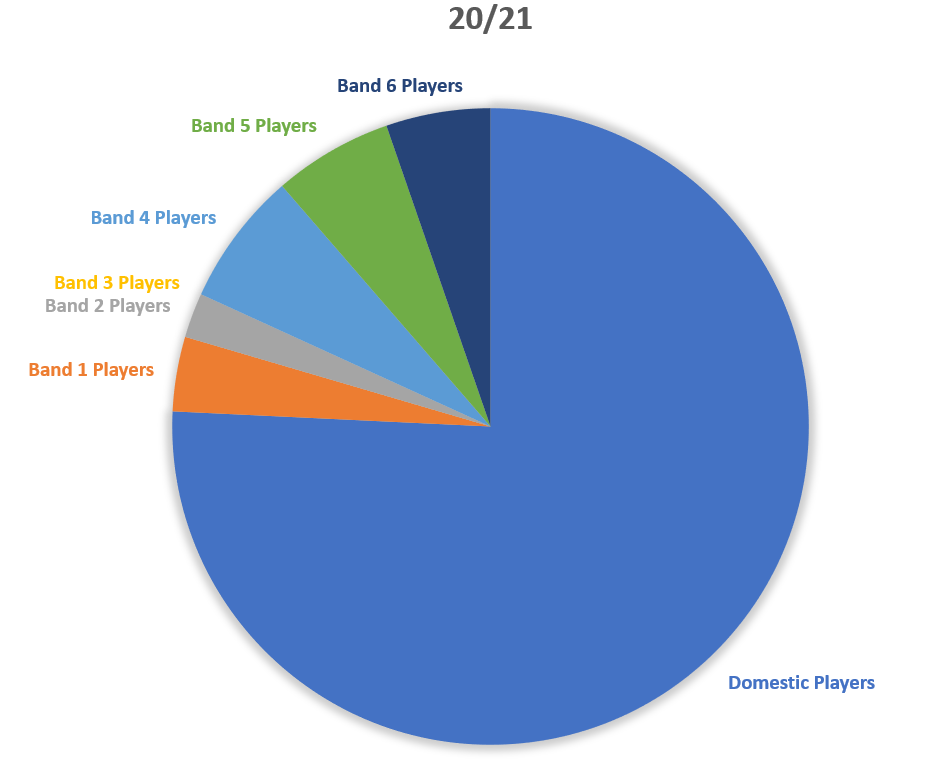

Of course, recruitment would’ve looked a lot different if the financial situation at the club was a lot different. FFP rules have constrained Blackburn with how much they can spend in transfer fees and wages to the extent that they have very much a bottom half budget for the Championship. This is proven by financial statements going back from the latest release for 2020/21 back through the last few years.

In terms of what the manager has some effect on, has the financial management in terms of transfer fees and wages spent been prudent?

It’s never that easy to judge financial data, especially within football. For the most part we have to rely upon “best guess” information, Football Manager data and calculations from the submissions to Companies House.

In Mowbray’s five-year tenure we have financial data from all years via submissions to Companies House. I have taken some of the key points from the Mowbray reign and summarised them in the following table.

Mowbray was powerless to prevent the losses increasing year-on-year for Blackburn Rovers. In reality, no manager could make much of a dent in a multi-million pound issue. However, the wage increase since he took charge is sitting at around 17%, not an insubtantial increase.

Also, in this time, the board sanctioned a couple of big-money fees for forwards Ben Brereton and Sam Gallagher. At the moment the Brereton deal in particular looks wise with a potential £10million+ fee being asked for his service, but also, with Gallagher signing a long term extension to his deal he is likely to provide a big service to the club and his performances, whilst inconsistent, are still important to the club.

Rovers have been able to manage the balance between debtors and creditors quite well over the Mowbray reign. It does look as though money generated through sales has been poor, but when you look at the squad inherited by Mowbray it was clear that it was going to take a while to develop talent that was actually worth anything. The sale of Adam Armstrong isn’t yet represented in these figures, but that clearly will make a big difference to the balance of money spent to money earned in player trading. A Brereton Diaz sale would do the same.

The year on year losses are bad, but mostly out of the control of the manager. The losses also highlight how the manager had to work within those means. The recruitment looks better than the bare numbers when considering the financial difficulties.

Just looking briefly into the squad wages that are not covered in the above financial accounts, over the summer of 2021 a lot of experienced and high earning players left the club. They were generally replaced by young players and loan signings. This meant that the squad actually cost less by wages paid. And yet, the improvement has continued for the club.

In essence, Mowbray has elicited the improvement in the league position in a highly competitive division whilst reducing the first team wage budget and, thanks mainly to the purchase and sale of Adam Armstrong, spending very little on player trading.

This prudent management has been an attempt to keep costs down but the owners have still had to continue to pump money into the club, as well as sell the training facility to themselves, to keep the wolves from the door. Again, this probably reflects well on the manager that such a situation didn’t seem to affect his work or the team’s performances (aside from the obvious part of having less quality on the pitch).

However, this has also meant that the infrastructure of the club hasn’t seen much, if any, renewal under Mowbray’s tenure. The stadium is beginning to feel dilapidated, the training grounds, though still good and able to sustain a senior team and a Category 1 Academy, has work that could be done. Realistically though, only a promotion into the Premier League would go any way to solving these problems.

Ultimately, this is something that Tony Mowbray did not come particularly close to achieving. This is where the frustrations often lie with the fan base. Mowbray has become famous on the messageboards and on social media for his “death spirals”. The actual statistics below set out the stark reality of Mowbray’s reign and the drop off in results in the second half of the season.

The hardest thing to try and do is to analyse where it has been going wrong for Mowbray. The points totals have been falling away, and in the last two seasons it has been a real decrease in goals scored that has been the issue. Chances created have fallen away as well, though not as steeply as the goals themselves.

Interestingly, these Mowbray teams have never dropped off in terms of expected points. So whilst the goals do dry up, the chances the team concedes also tend to reduce and therefore matches are more narrow in their expected outcomes. Therefore it only takes a mistake or luck to go against you to turn a positive result into a negative one. There’s also the point that in 19/20 and 21/22 the team massively overperformed their xPts and a reversion to the mean in those cases were to be expected.

Season 21/22 will definitely be the most painful of the falls because of the position that the club found themselves in. In January it would actually have taken a record poor effort for Rovers to miss out on the playoffs. To not even be in with a shout by the final day must be very painful for all concerned.

So what of the relationship between the manager and the fanbase?

The relationship between Mowbray and the Blackburn fans has never reached the point where he lost the support of all the fans, or perhaps even the majority of the stadium-going fans, but there have been definite tensions with the fanbase on numerous occasions about his leadership of the team.

On many occasions the #mowbrayout has been seen and when the club goes 15 matches without a win, displays relegation form for a sustained period of time to drop from automatic promotion to outside the playoffs and sustains it’s biggest ever home defeat then perhaps this is understandable. Indeed, that long winless run came when fans were not allowed in stadiums. Had this not been the case then there may well have been a lot more pressure put on the decision makers to review the managerial situation.

There is also a thought that Mowbray’s demeanour in press conferences and interviews has worked against him in his relationship with the fans. Whilst I don’t subscribe to that theory myself I can understand the frustrations of some fans with this.

It would appear though that upon his departure there is a feeling of gratitude amongst most fans for Mowbray’s service to the club for over 5 years. Most agree that he is a good man with integrity and morals that has represented the club in the right way. Some are glad to see the back of him as well of course as is the nature of a fan base and, indeed, of social media.

It wouldn’t be an Andy Watson blog post without finishing with some data. Whilst points are the currency of football and points make prizes they are not always the best way of measuring improvement.

Using expected goals as a measure we are able to track Rovers’ performances since their return to the Championship and establish their xG for and against over that period on a rolling average.

The overall trend is one of defensive improvement. From conceding over 1.5xG per 90 in the first season back in the Championship, Blackburn ended Mowbray’s reign conceding fewer than 1xG per 90.

The chance creation suffered on average though. There were some spikes of immense chance creation, usually at the beginning of seasons, but also a couple of periods of real struggles in creating chances.

We are also able to compare the xG difference to the actual goal difference over the different seasons to see how much the team over/under performed with their points won against chances created.

This chart really does demonstrate the improvement over time really well. Showing the xG difference alongside the goal difference proves that the increase, especially over the last two seasons is not a fluke.

The improvement has slowed somewhat towards the end of Mowbray’s reign, and ultimately, may well be part of the reason why we see the parting of the ways now.

Certainly looking at this chart, it does appear to be a good way of viewing a manager’s reign in totality.

Overall Conclusions

Some may think that this whole blog post is a bit mad. A manager is judged good or bad based upon how successful they are. The problem is that everyone has their own opinion and judgement on what that means to them.

Some Rovers fans will say Mowbray will never take Blackburn Rovers to the Premier League, therefore he needs to be replaced. Some will say that he’s done a good job and should stay. The trouble, of course, is that those judgement calls are not mutually exclusive and I daresay that a lot of Rovers fans believe both of those statements to be true, i.e. Mowbray has done a good job but isn’t the man to lead the club back to the Premier League.

What I have attempted to do, using Mowbray and Blackburn as a case study, is to come up with some rules or brackets by which we can apply some kind of measurement to how well or badly a club has performed under a manager.

In Tony Mowbray’s case, these rules suggest that he has been a successful manager for Blackburn Rovers:

Is the club’s position in the ladder better or worse than when they joined? Tick

Does the playing staff look a better group at the end of the tenure? Tick

Could the player recruitment be described as over 50% effective? Average

What has the financial management at the club been like in terms of transfer and wage spend? Good

Has there been any infrastructure improvement in the club? Average

Are there any assets left behind that may allow the club to progress at the end of the tenure? Tick

What is/has the relationship between the fans and the manager like/been like? Average

Positive performance data Latterly, tick

Worryingly though I am still not sure it helps me assess how good a manager really is and it certainly doesn’t help to predict how successful they will be in future. I think that the fit and the circumstances between a manager and the club that they are in are totally unique and some things are just not applicable from job to job.

However, what I would say is that if a club were looking to employ Tony Mowbray in future then they can be satisfied that the job he did at Blackburn Rovers was one of competency, financial prudence and good sense.

If anyone would like a similar study done on their manager or on a manager of their choosing please get in touch.

Appendix